- Home

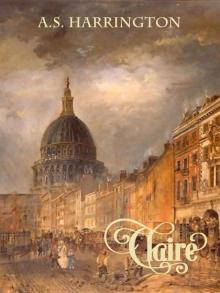

- A. S. Harrington

Claire Page 22

Claire Read online

Page 22

Out in the ocean, like white feathers on a blue hat, like ivory inlaid into sapphires, were sails, three, four, seven, eight of them. Eight. Eight sails.

But the white feathers were tinted; the ivory was gold. She raised a hand to shade her eyes against the bright sun, the sapphire water turning to silver as a gentle, warm breeze blew across her face from the Atlantic. The ships were not moving; no— the ships, graceful, leaping, golden, were moving, but not toward land. The ships—

She stared, disbelieving; as she stared she saw orange burst from the blue water, in a subdued sigh of doom, as the ninth one appeared. For what she had seen was not the white of their sails; she had counted eight, because the ninth one was white. What she had seen was the orange glow of fire, and as the ninth one had exploded, with that faint thunder hardly distinguishable from the guns behind her, she had seen it also, at last.

As she watched, a plume of black smoke lifted heavenward over the faultless ocean; she stared at the ships for a moment longer, and then her slender hand left the cool stucco. She ran across the mosaic tiles, past the small walled garden, back into the street, and up the hill.

“Claudia!” She ran breathlessly inside the house, past the fig tree, calling out for her sister over the voices of the wounded in the streets. “Claudia!”

“Claire!” The calm figure appeared in the doorway, with a bucket of water in her hand and a basket of bandages over her arm. “What is it?”

“Rajat! Where is Rajat?” Claire asked, her heart in her throat, as she met her sister in the doorway and grasped her by the arms.

“Rajat? He is— ” Claudia looked around. “He is asleep. He came here with us— ”

“He is not here! The ships— those ships, out at sea— I have just been to the church and seen them— they are burning, everyone of the them, on fire!”

“Oh, dear God,” came Claudia’s soft voice. She spoke to Consuela beside her, who shook her head worriedly.

“He’s gone?” said Claire, in a quieter voice.

“He went back,” Claudia said, staring in disbelief at her sister’s serious face. “He went back.”

Claire dropped her hands from her sister’s arms on an enormous sigh. “He left us this morning at the church. I remember when we came here that he wasn’t with us. I remember thinking of it, only I was— ” She turned away, staring out into the street past the garden gate. “There’s been fighting, Claudia, yesterday and today, in the hills. The English are here.”

“Yes, I know,” said her sister, and went past her quietly with her arms full of bandages and out into the street.

They could have worked all night, she supposed, for there were wounded in every house, in every square foot in the village.

They stopped finally around dusk, and went back to the widow’s house. Somehow the old woman had found them clothes, and had brought up a large basin of fresh water for them to bathe. At last they washed off the blood of the wounded and the salt of the ocean; it came out of their hair, and out of their skin. They dressed in sturdy clothes, in the wide black skirts and full blouses of Portuguese peasant women, and wound thick, wide scarves loosely over their heads and over their shoulders, and ate figs and apricots and cheese and fish soup that the widow had prepared for them.

The battle was over. The French had been defeated about three miles from the village, and General Junot had already met General Moore of the English expeditionary forces in his tent to offer his sword. The cannon had stopped; the French were in retreat, toward Alpiarca across the Tagus.

Out in the sea nine ships still burned, vaguely, against a full moon rising behind them. As soon as Junot had received word of the disaster, he had called his guns to halt and had instituted his own retreat, for those ships had been his last hope.

“I know they’re here,” said Claire suddenly over her cheese, staring at her sister. The four women had been hungry but had eaten silently, thinking of Rajat and the ships. “I shall find someone to lead me to the field headquarters, for I know they are here.”

Claudia nodded. “Yes, I am certain that they are,” she said. “I suppose that Rajat would tell us that the good and bad march side by side. Perhaps out of all this death and dying here,” she added quietly, “we shall find them living.”

They could find but one donkey, and they paid its owner half-a-dozen English gold guineas, which he took gratefully. The sisters climbed on it and set out in the direction that one of the English soldiers had given them.

It would have been difficult to find their way had not there been a steady stream of torches and wounded soldiers coming in toward the town. They plodded over the tree-covered hills, leaves rustling overhead, a low murmur from the passing soldiery, accompanied by the ancient, pleasant evening song of crickets.

The sisters stopped now and then to ask for news; Claire would say, “Do you know Lord Banning? Have you seen him?” after they had heard what hill had been taken when, and how many had been lost, and what time surrender had come. The soldiers would exclaim over two Portuguese peasant women on a donkey, as they heard a cultured English voice inquiring after an English peer, and then would point behind them, where Moore’s field tent still sat in the middle of his camp at the edge of two hills beneath the trees.

At last they reached the outskirts of the English camp, some several thousand men, and the donkey plodded through the lines of good English regulars preparing for a night in the field. After asking the way once more, the two women finally glimpsed the map tent at the end of a small path that had been worn in the last four days from the constant tramp of boots.

Claire slid down off the horse as they drew up; there was a guard standing beside the tent, eating his supper. “Excuse me,” she said politely, and he looked up in surprise. “I am looking for Lord Banning and Lord Merrill; I believe that Lord Banning is attached to the general’s staff as an interpreter?”

The tent flap was thrown open and Moore himself stood there, his face cast into shadow by the lamp behind him. “Good god,” he said blankly, staring at the peasant figures and their donkey.

“Excuse me,” repeated Claire. “I am Lady Banning; is my husband here?”

“Drew?” said Moore. He was middle-aged and slightly stout around the middle, and very, very tired. “Varian Drew? You’re Drew’s wife?”

“Yes,” she said, throwing her scarf back over her shoulders. “I am Claire Drew. I have come to see my husband.”

“Good god,” repeated the soldier slowly, staring still. He caught himself after a second; “Oh, apologies; come inside, will you? Cup of tea? I’m dreadfully sorry, but I’m all out of sugar.”

“Is Varian here?”

“No, he’s not.”

“Where is he?” she asked clearly.

“I don’t know; haven’t seen him all day. Although I think he had something to do with those ships— Have you heard about the French ships that were waiting for Junot off the coast? Several brigs and at least a frigate or two! Some servant boy, Eastern, I think, came to him this morning, and he and Merrill went off to see about something. He said ships, so I rather— ”

A small cry burst from the woman holding the donkey. “No! Not— ” Both women, stunned, fell silent and turned to each other as Lady Banning covered her mouth with her hands, and then held each other desperately as General Moore asked if there was anything wrong, and would they care to come inside, and if perhaps he could offer them a cup of tea, if they didn’t mind that he hadn’t any sugar.

chapter twelve

All Days Are Nights

Varian Drew had never doubted that they could set the ships afire; that had been child’s play. A fishing boat had been anchored about a mile off the port bow of the land-most merchant ship, doing a bit of innocuous fishing; Drew, Merrill, and Rajat rowed out toward it from the village in the rowboat that Rajat had so recently appropriated. The rowboat was small and not very noticeable, and the fishing boat had given them cover until the last possible moment. No one thought much

about a rowboat from the village.

Setting the ships afire had been easy. According to Rajat, the French weren’t expecting any action until they approached Lisbon, and at least the merchantmen crews had eaten and drunk to excess the evening before. Loaded with munitions, with crates of shot and bales of hay for horses below and with barrels of tar and gunpowder stacked under oilskins on the deck, the ships were full of flammables, and once lit, the fires spread quickly. By the time the sails were engulfed on one ship the three men had already reached the next. Panic set in quickly as the first two ships began to burn, and one of the warships tried to come about to fire a volley at the enemy . . . but they could not find the enemy. There was no enemy on the shore, and no English ship had appeared over the horizon. No one was looking for three men in a rowboat.

Merrill, Drew, and Rajat never made it to the last of the warships, but it didn’t matter; the last two of the French navy guns were anchored so close together that the fire from one spread instantly to the other.

In fact, setting the fires was child’s play. But escaping after it was over, now that was a different proposition altogether, and Drew never really thought that they would make it back. But somehow in the chaos and confusion, with French sailors everywhere in the water, with local fishing vessels all around, the rowboat was simply ignored.

It was with a sigh and a profound sense of dread that he set foot once more on the sandy beach an hour after the long summer sunset as all the fishing boats came into the harbor. Most bore French sailors who had managed to escape the conflagration, picked up by fishermen, ancient silent Portuguese who were brothers to all sailors, no matter their nationality.

The three of them made the journey back to the village without speaking, with a great cavernous silence over them. They had not once mentioned Claire or Claudia or their servant women, and those unspoken words lay between them now, over them, like a heavy cloak, heavy and wet like their clothes.

They came ashore silently in the dark; Tony Merrill gave the owner of the fishing boat another handful of guineas, and thanked him once again, and he only nodded and smiled at the large gentleman’s attempts at his language. Varian Drew strode ahead, up the rocky beach, past the torch-lit seawall, past a multitude of English soldiers in varying degrees of discomfort, up the hill toward the church, with Rajat and Merrill silent behind him. With a clatter of heavy boots on the mosaics of the porch, the stucco gray and black and pink in the reflection of the torches lighting the town, the golden-haired Englishman bent slightly beneath the low, open door and went silently, purposefully down the wide center aisle, past the supplicants kneeling in the shadows of the darkened church, toward the altar, where the priest was lighting candles for the dead and dying.

“There are some Englishwomen here,” Drew said flatly, without greeting.

The priest turned and looked at the exhausted, care-worn face in the light of his candles. “Yes; I took them to the widow’s house up the hill. The house with the fig tree in the garden, beneath an arch, there,” he said, motioning vaguely with his arm.

“How many women?”

“Four,” said the priest, and turned back toward his praying, and closed his eyes as the golden-haired, slight damp giant went back outside, limping a little in spite of his magnificent physique, his broad shoulders bent slightly with exhaustion.

Rajat and Tony Merrill were standing in the cool black shadows of the portico. As he passed them, Varian Drew said, “They’ve gone up the hill,” quietly, his face unreadable in the darkness, and went up the narrow, steep, crowded street, weaving among the wounded and the torchbearers and the horses and carts of the English and through the raucous night.

The house was not hard to find; Drew saw the fig tree past a small arched gateway in a courtyard full of exotic blooms. With a grim expression, he rang the bell beside the gate, and in a moment, a large peasant woman appeared on the other side of the courtyard and then came quickly toward him. It was Consuela.

She exclaimed over him; she greeted him with tears in her eyes, and then exclaimed over Rajat, and then over Lord Merrill, and told Rajat that they had seen the ships burning and had given him up for dead. Then Merrill asked her quietly if Claire and Claudia were inside.

“No, they have gone up into the hills to search for you,” she said, smiling, and patting Rajat’s shoulder with her broad hand once again. “This evening, on a donkey.”

An immense, slightly philosophical sigh from Merrill. “Good god, we may chase them all the way back to England.”

“If they’ve reached Moore,” said Banning in a low, expressionless voice, “they’ll know that we went out to the ships today. And Moore— ”

“Suppose we stroll out and find them?” suggested Merrill without ado. “I don’t know if Claudia will even speak to me in my present state of sea-salted soddenness, but I for one am damned tired of chasing them. Let’s go.”

“Rajat, find yourself somewhere to sleep,” said Drew quietly, and clasped his servant’s shoulder, and then he and Tony Merrill continued up the narrow street toward the edge of the village.

“You know, Varian, just the fact that they’ve come says something,” began Merrill, after they had walked in utter, absolute silence a half mile from the village, against the steady procession of English soldiers. Tony had spent the last three days trying to convince Varian Drew to return to England, and, in spite of a light reference to his wife’s state of mind and a spilt glass of laudanum, had been unsuccessful. Good god, Drew’s father had tried to kill himself; it had seemed unduly cruel to burden his friend with his wife’s attempt also.

“It says,” came Drew’s quiet, harsh voice, “that she felt guilty enough and was foolish enough to do something that I hope a ten-year-old would have had the sense to think better of— ”

“Varian,” sighed Tony, even his vast patience wearing thin, “I suppose I oughtn’t to tell you, but occasionally you are a stick-head. She loves you; you are obviously mad over her. I cannot think what all this dither is about. Take her home and make her happy.”

They passed a group of soldiers in silence; the procession was thinning now, and the bulk of the English were settling down to sleep after a very long day. “Yes; it would be the logical thing to do, wouldn’t it?” Varian said finally, addressing himself more to Tony’s nature than to the situation.

“They’ve been through hell to get here,” came Merrill’s voice, perhaps a little sterner. “I don’t take it lightly, although I am coming to seriously doubt what I had always supposed to be an innate rationality in my wife. I— ” He tensed in midstride. “My god.”

Up the hill, coming toward them from beneath a row of olive trees at the end of a line of six or eight soldiers bearing a torch, were two peasant women, one of them riding a donkey, the other walking along beside her, both of them with scarves over their heads, drawn down close over their faces.

Tony Merrill laid a sudden hand on his friend’s arm and met his eyes in the darkness; then he stared up the hill again, intently, and called out, “Claudia? Claudia!” in a decidedly uncalm voice, and quickened his footsteps up the path toward her, in a long pacing stride that was almost a run.

The woman walking, holding to the donkey’s bridle, halted instantly at the sound of her name, and threw back her scarf and raised her head. She saw a tall, broad-shouldered figure coming toward her, brushing past soldiers along the path beneath the apricot trees. That damp, crumpled shirt and dark head was the most wonderful sight she ever expected to see; with a small cry she picked up her full peasant skirts and raced down the hill and met him, fell into his arms, his name on her lips, and clung to him in the darkness, burying her cheek on his damp shoulder, as his arms closed possessively, roughly, crushingly around her.

“My darling Claudia,” came an unsteady voice in her ear. “You should not have; and you are the bravest woman on this earth,” he said in a whisper, as she raised her head. A long, silent, wordless gaze in the darkness beneath the apricot trees, a

nd then Tony Merrill, no longer calm, nor placid, his gray eyes burning with an open passion, bent his head and kissed his wife with some fierce emotion that he could no longer hold back.

“Tony!” Claudia answered, as his mouth, demanding, came down on hers and his arms clasped so tight around her that she could hardly breathe, nor did she care. For her heart was singing as she embraced her husband, as a fountain of secret, silent love poetry burst forth into being between them.

And up on the hill the donkey had stopped; a woman slid down off the blanket on its back and stood there, silent, watching, waiting in the darkness. Below her a motionless figure stood as if carved of stone, the golden head glittering briefly as the soldier passed him with the torch and continued down the hill.

Then he turned, quickly, and strode away behind the soldiers. The woman, weeping silently, followed slowly down the hill, past her sister, without seeing her, watching that receding figure through a blurring film of tears.

By morning, six English Royal Navy man o’ wars had anchored within sighting distance of the shore at Vimeiro, and the English began the long process of removing their wounded, as General John Moore and the remainder of his expeditionary force packed up camp to return to his headquarters in Lisbon. In another month the French would be formally out of Portugal, at least for a while, by virtue of the Convention of Cíntra, signed in the palace of that magnificent outburst of rock up from the coastal plains. But for the moment, there were practical matters to be attended to, supplies to be unloaded, wounded to be shipped home— and, thank God, sugar to be had off one of those warships.

The queue from the beach seemed endless. Tony Merrill had been down first thing and secured passage for the seven of them to go home, and had been met with a polite and respectful offer of accommodations onboard the vessel of Sir Robert Calder, flagship commander. Merrill went back up the hill and kissed his wife, again, and told her to pack, that they were going home, but she only laughed at him with that particular light in her eyes that so set him on fire and told him, “But darling, I haven’t anything to pack,” her face aglow, which caused him to kiss her once more.

Claire

Claire