- Home

- A. S. Harrington

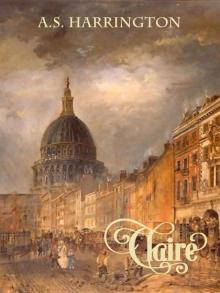

Claire

Claire Read online

Claire

This book first published in 2014.

Copyright© 2014, 2015 A.S. Harrington

All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1 Home from Abroad

Chapter 2 The Deceit

Chapter 3 A Gentle Assault

Chapter 4 Anger and Accusations

Chapter 5 Sensibility Put to Rout

Chapter 6 Plans, Proposals, and Patience Gone Awry

Chapter 7 The Letters

Chapter 8 Calamities and Errors

Chapter 9 An Unhappy Parting

Chapter 10 A Difficult Journey

Chapter 11 Treading on the Tail of the Tiger

Chapter 12 All Days Are Nights

Chapter 13 Against the Will of Nature

Chapter 14 The Hosts in Motion

Chapter 15 A Gradual Advancement

Epilogue

prologue

The man on Merrill’s terrace, fair-haired and slight, leaned rather heavily on a cane, although he was not yet middle-aged, nor did he seem particularly infirm, unless one saw his eyes. They were ice-blue, shaded and shadowed with some recent agony, some hardly-recovered-from sickness, some hovering pain. Perhaps it was this that made one look twice at his pale face, that made one glance again at the sharp outline of his cheekbones and his brow against those thick-lashed sapphire-colored eyes.

He was tall, with golden hair that shone faintly copper and silver against the early morning sun as he left the spacious terrace of Merrill Hall and ventured out, limping slightly, into the dewy garden toward the rose bed and the lake. In spite of his well-cut coat and his neat cravat, he was somehow out-of-place in this calm, peaceful Essex morning, lethargic in a dewy silence, placid and cloudless, the breeze sighing over a bee here and a wren there.

He limped; he favored his right foot with painful care and seemed a little unaccustomed to the cane, although he leaned heavily on it as he walked. He looked as though he had been ill; there was the memory of broad shoulders and a disappeared athletic litheness in his stance as he bent slightly over the cane at the stone steps past the roses. He was not quite thirty years of age, although he seemed older; if there had been a shimmer of gray instead of that bright gold in the hair at his temples, one would have guessed his age at forty, or even older.

As he paused briefly to view the roses, the blue eyes drifted up from the pinks and reds of the hybrids to gaze out past Merrill Park toward Finchingfield, which lay just out of sight toward the east. He breathed in the heady crystalline morning air, and leant on his cane once again to venture out past the rose bed toward the garden wall, past a tall shrubbery and a bed of brilliant tulips and lilies and iris. He halted instantly.

“Oh!”

There was a child in the flowers; she was plump and dark-haired, with eyes very much the color of his and a faint sprinkling of freckles over her white skin. She gazed up at him with a distinctly distressed look on her round little face, as though he had caught her at some horrible faux-pas.

“Good morning,” he said politely.

“Oh!” she repeated, eyeing his cane with very large blue eyes and then backing away into the tulips. She wore a plain, slightly faded blue muslin dress, and she had a basket full of tulips over her arm, a pair of shears in her hand, and a very guilty look on her face.

“Who are you?” he inquired in that pleasant voice of his and gave her an encouraging smile. She was fourteen or fifteen, perhaps; her dark hair was caught up in two pigtails on either side of a childishly round face.

“I— ” A frank blue gaze, with one dark, straight, thick eyebrow slightly raised, met his. She hesitated, and then she said firmly, “I’m Susie— John-gardener’s daughter.”

“Very pleased to meet you, Susie,” he said, bowing slightly. “And who is this?” he inquired, nodding at the furry white beast who had instantly found his shiny black boots.

“Sully!” she whispered fiercely and gave the man a craven look, and then suddenly pushed her shears into her basket and stooped down and picked up the offensive animal and tucked him, meowing angrily, under her arm. “Stop that this instant, you plaguey creature! I told you not to come!” The girl’s uncertain blue gaze fell upon his face again as if she suspected he had heard the most of her whispered admonition, which the cat seemed to take in great offense. “I’m sorry!” she said aloud, just as Sully, his pride in tatters, gave a great lunge straight out of her arms, wreaking instant disaster as he sprinted out of the basket, upending tulips and iris in a shower of color over the girl and disappearing sulkily into the hedges. “Sully! Sully!”

“We’ve offended him, I see!” observed the golden-haired man, laughing, and would have stooped, a little clumsily, to help her gather up her flowers, but she told him instantly, firmly, with that tiny guilt in her blue eyes as she knelt, that he should not bother.

“You won’t tell that I’ve been here, will you?” she pleaded.

“Do you not live here?”

“At Merrill Hall?” In a second of reconsideration she glanced up, and then the blue eyes bent again and shaded themselves quickly from his gaze. “Not— precisely,” she said, swallowing uncomfortably and throwing the flowers quickly into her basket without the least care for them. “Well— sort of,” she amended, after a glance at his face above her. “You’re visiting, aren’t you?”

“Yes, just for a few days,” he nodded pleasantly, doubting very strongly that her finely-tutored language belonged to the gardener’s daughter. “I’ve been recuperating with this foot of mine, you see,” he added.

She retrieved the last blossom and put the basket firmly over her arm. “Well, I hope you have a lovely time,” she nodded without looking at him and was gone past the garden wall and the shrubbery in a rustle of faded muslin and wet grass, calling out in an enraged whisper, “Sully! Sully! Disagreeable brute! I shall strangle you! Come here!” and causing the gentleman to chuckle as he continued his stroll.

“Oh, Chloe, you will never guess!” A pair of mischievous blue eyes, very much like those of the child calling herself Susie John-gardener’s daughter, looked up from a very dull page of watercolors at that breathless voice.

“Claire!” exclaimed the girl at the table, jumping up, and very nearly upsetting the paints. “I wondered where you had got to!” She gasped. “You’ve been stealing Merrill’s flowers again!” she accused, placing her slender hands on her hips and glowering at her younger sister.

“Oh, Chloe, I’ve seen him! You will never believe it!”

“Seen him?” uttered the pretty girl at the table. She was of medium height, with dark hair and blue eyes like this other uncertainly-named creature in the doorway, only Chloe was no longer plump or childish. She was a very pretty young twenty years of age, with a teasing smile and a tiny waist, and she was madly, desperately in love with Timothy Dickinson, one of her father’s crew, who had come with him home to visit. That teasing blue gaze turned suddenly agonized; with an unsteady voice she said, “Not— not Lord Banning?”

“Oh, yes! He walks with a cane, can you believe it! And he is very old!”

“Oh, Claire, no, no! I cannot bear it! If Papa makes me do it, I swear I will throw myself into the mill-pond first!”

“Chloe, don’t be such a goose!” The plump child came inside; she was as tall as her sister, although she could not lay claim to Chloe’s delicate reediness nor her exquisite figure. She set her basket carelessly on the table, plopped down ungracefully into a chair, and said, “Perhaps Papa will decide on Claudia, for she ought

to go next, you know! I am certain that if you say no, Papa won’t have another word on it. I cannot believe that he is as blind to this— this tendre of yours as you think!”

“Oh, no!” said Chloe, and began to pace about the schoolroom, a smallish, plain chamber full of books and this table, with pleasant frilly white curtains at the gabled window and a rag rug on the floor, and room for very little else. “Timothy has said nothing! I would die before I would breathe a word of it to Papa, for if I have mistaken his feelings, and he is only flirting or somesuch, he will very likely laugh at Papa, and then I should be in the soup!”

“Chloe! Don’t carry on so; you’re giving me the cross-eye! Will you sit down!” burst out her youngest sister. She pulled a tulip from the basket and set it in the vase in the center of the table, and then, with a faint lightening of her expression, began arranging her flowers. The straight, dark brows frowned faintly in concentration. “I have already said that Claudia ought to be next; Clytie and Cleo have married just in a row, and Claudia is next. I cannot see what there is to fret over; and you know very well that Papa shan’t make you do it! He is not at all that way!”

With a heartrending sigh, Chloe turned to her sister. “Of course he is not! But Claudia! Oh, Claire, you know she will go straight into a decline and die if Papa marries her to anyone who does not quote Chaucer in his sleep and live chiefly on quatrains and philosophy! She has told me so already!”

“Well, I cannot think there will be anyone like that to find his way to Essex!” said the practical Claire. “And if he does, he very likely will be penniless, and you should know that penniless scholars are not much in Papa’s style!”

“Lord Banning is penniless!” pointed out Chloe.

“Well, yes, but he has a title, Chloe! Altogether different! Don’t you wish to be Lady Banning?” inquired the steadfast Claire, engrossed in her stolen flowers.

“No! I wish to be Mrs Timothy Dickinson!” burst out Chloe.

“You had just ought,” came a voice from the doorway, “to open the window if you wish to announce it to the neighborhood, Chloe!”

“Claudia!” Chloe exclaimed, her heart flying to her throat. “Oh, you have given me a fright!”

A smallish dark-haired girl, with the same blue eyes and white skin as her sisters, came inside, her spectacles in one hand and King Henry IV in the other. “I wish you will close the door when you intend to shout, for I cannot hear myself think when you are carrying on, Chloe,” she said quietly.

“Oh, do come in, Claudia,” came Claire’s voice. She twisted in her chair and turned her plump face on her other sister. “I’ve seen him! He was walking in Merrill’s garden this morning, and he gave me such a stare that I thought I would faint! I— I told him I was the gardener’s daughter, and then that dreadful cat jumped on his boots, and I ditched my basket, and when I find that stupid beast, I shall skin him alive!”

“You did what?” inquired the sister from the doorway. The three of them were not at all alike, in spite of those clear blue eyes and their dark hair; Claire, who was eighteen, and still stricken with baby fat, almost seemed the eldest beside Chloe’s mischievous lack of sense and Claudia’s studious preoccupation.

“I— Well, I— I know I promised, Claudia,” stammered Claire, flushing and averting her face. “But Merrill has so many! I am certain he doesn’t miss just a few, you know, a tulip here and there— There are hundreds and thousands of flowers in his garden, and I cannot think he would care if he knew!”

“Claire Ffawlkes, it is stealing!” said Claudia sternly. She came inside the schoolroom and closed the door. “And you know very well that Papa would ring a peal over you if he found you out, no matter does Lord Merrill care or not! You had better not let Papa see those flowers, for he shall guess instantly where they have come from, and I shan’t feel the least sympathy for you if he blisters you!”

“Oh, Claudia, I know!” The child propped her dimpled elbows on the table and rested a penitent face in her hands and peered out the window. “I know! And I shan’t do it again! I promise!”

“But Claudia!” interrupted Chloe, who had again taken up her pacing. “She’s seen him, no matter what she was doing there, and it is just as dreadful as we had imagined! He has a cane, and he is quite old!”

“I believe,” came Claudia’s quiet voice, “that he suffered some sort of an injury when his father died; Papa has said that he almost died himself. And of course, he’s been in very poor conditions in prison; I shouldn’t wonder that he has had a difficult recovery!”

“I cannot but wonder why Papa is so determined to marry one of us to him!” exclaimed Chloe. “Surely Papa cannot think that marrying his daughter to a debtor will increase his stature, no matter Lord Banning’s father was a friend of his!”

“It was Lord Banning’s father’s debts, not his, you know, that landed him in prison,” said Claudia. She came over to the table and picked up an iris. “And stealing is just as bad as being in debt!” she added pointedly. “If Merrill has you arrested, I shan’t be surprised!”

“Merrill is much too kind!” Claire thought for a moment, and then said, “I wouldn’t mind to marry him, you know!”

“He doesn’t need a rich wife!” said Chloe. “He has loads of money!”

“Well, it does seem that Papa would be a little more nice in his tastes, than hauling a title out of prison just to get it!” retorted Claire.

“Claire!” Claudia sighed, and regarded her sister with a slightly rueful smile that gave a subtle change to her face, and granted her some of Chloe’s mischievousness. “I wish you will learn to think before you speak! If you spit out something like that tomorrow night while he is here for dinner, he very likely will take an instant dislike to all of us!” Another sigh; this time her face fell into a quiet unhappiness. “And I suppose things will be bad enough without his disliking us! I cannot imagine why,” she said, shaking her dark head, “Papa is so determined to marry us well! I am certain I shall be miserable, and it doesn’t seem worth it, does it!”

“Poor Claudia!” said Claire sympathetically. “You shan’t hate it so much, shall you?”

There was a moment of stricken silence; then Claudia, that calm, perennially serene bulwark of stability in this household of females, burst into tears. “Oh, but I shall! I shall! I shall hate it, and I am far too timid to stand up to Papa!”

“Oh, Claudia, dear, don’t cry!” said Chloe instantly, putting her arm around her elder sister’s shoulder. “I— I shall marry him, instead, for I will not see you so unhappy!” she said resolutely, and then she too burst into tears.

A very distressed Claire looked on for a moment and then went back to arranging her flowers. “I think the both of you are perfect ninnies,” she said bluntly. “If you don’t want to marry him, say so! But I cannot see it will be so bad! Clytie and Cleo are perfectly happy!”

“You don’t understand,” said a tearful Claudia.

“Clytie is desperately in love with Phillip! And Cleo is desperately in love with John Haversham, and I,” sobbed Chloe, “am desperately in love with Timothy Dickinson! Oh, Claudia! What are we going to do?”

“I shall go downstairs and insist on seeing Papa, and I shall tell him that neither of you want him, and that he shall simply have to find someone else!” said Claire without much ado. “I cannot see that there is the least thing to play a tragedy over!”

“Oh, go away!” sobbed Chloe. “You have the sensibilities of— of a brick!”

Her plump young sister sat very still for a moment. There was the faintest tremble in that square chin, and then the full mouth firmed itself resolutely, and the dimpled elbows were removed from the schoolroom table, now littered with tulips and iris, and Miss Claire Ffawlkes stood and went quietly out of the room.

With Sully locked safely in the kitchen cellar and a basket— which, to be truthful, was quite empty— over her arm, Claire lay in wait the next morning in the tulip bed. Her heart began to thud as she saw the fair-ha

ired man limp outside onto Merrill’s pretty terrace, past boxes of geraniums and a great many morning glories and all sorts of white roses and pink peonies and masses of blooming dahlias and such, just the sort of terrace she had often dreamed of having all to herself. Then she swallowed firmly the lump in her throat as he came down past the roses, his cane tapping lightly on the bricked walk. He took the two or three steps past the hedgery, his golden head alight in the early morning sun, his morning coat impeccable, his cravat well-done. She drew in a great shaking breath as he limped down the walk toward the bulb bed, but when he caught sight of her, with that faintly surprised look that told her that he had seen her, she found herself quite speechless.

“Susie, wasn’t it?”

Claire took another deep breath. “Well— No, not precisely,” she stammered, flushing, and suddenly wished she had put on another dress, besides this blue thing that had come from Clytie and Cleo down to Claudia and Chloe, and thence to her. It was a bit tight; she was not thin like her sisters, and she hated it, and she hadn’t the least idea what she ought to say to him.

A small smile lightened his gaunt face. “No, I didn’t really think you were, you know,” he said. “Have you brought Sully, or did you strangle him, as you intended?”

“Oh—! I— No, he’s quite safe at home!” she exclaimed. “I’ve locked him in the cellar this morning!”

“Have you? Excellent idea!” he nodded.

“And in fact I oughtn’t to be here at all, you know,” she said suddenly. “I— ”

He gave her a secretive wink. “I didn’t tell.”

“You’re very kind! For Claudia thinks I ought to be arrested!”

“For taking Tony’s flowers?” he chuckled. “I daresay he won’t hold it against you. Who is Claudia?”

“She is— ” The blue eyes flew to his face and then fixed themselves on the top button of his waistcoat. “She is my sister. I am Claire Ffawlkes; there’s five of us, you know.”

“Ffawlkes?” The pleasant expression on his face faded a little. “You’re one of Sir Colbert’s daughters?”

Claire

Claire